March 24, 2024 Bridge Team

Navigating Tuberculosis and Social Stigma:

Insights from Sri Lanka’s Health Sector and Marginalized Communities

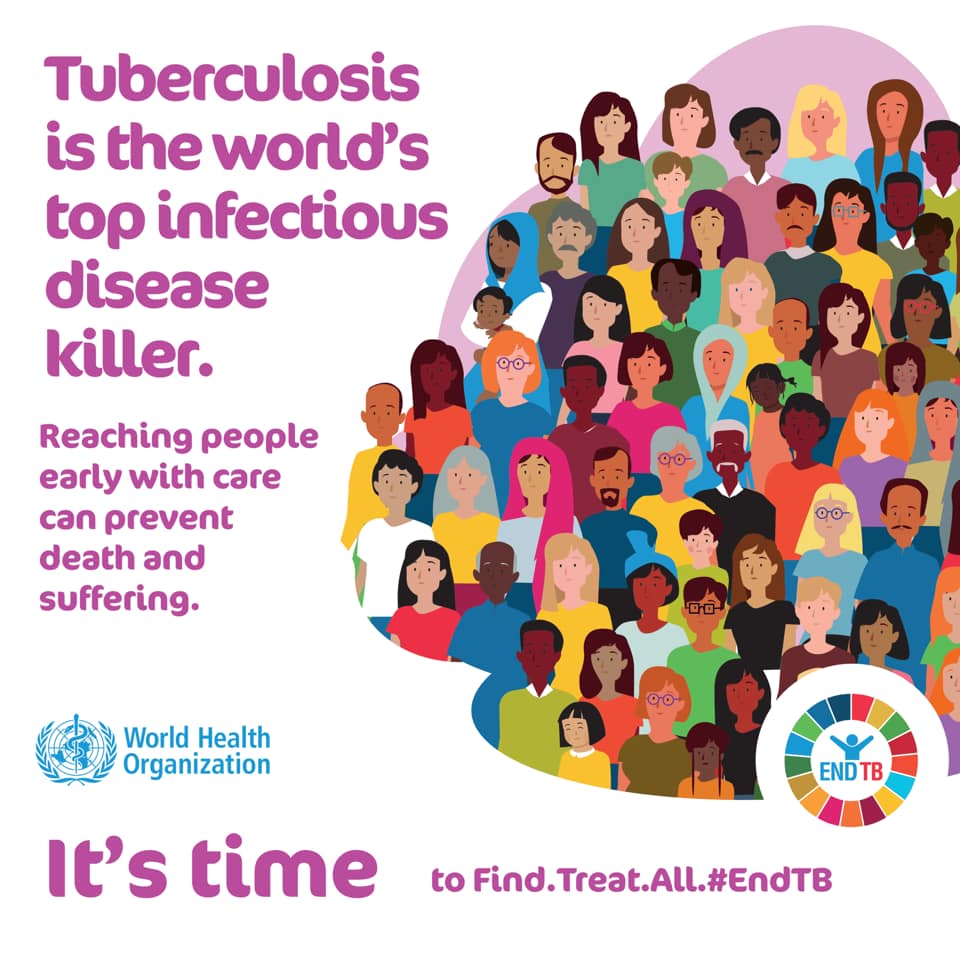

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant global infectious disease, notorious for its deadly impact and association with poverty, which often compels individuals to hide their symptoms to avoid social stigma. In Sri Lanka, TB ranks as the second most prevalent infectious disease after dengue.

The LGBTIQ community in Sri Lanka encounters discrimination and stigma. Accessing medical services, including TB clinics, is particularly challenging for them due to concerns about getting scrutinized for their sexual orientation or expression.

According to the Ministry of Health, Nutrition, and Indigenous Medicine’s Epidemiology Unit, there were an estimated 3.8 TB-related fatalities per 100,000 of the population by the end of 2020. Despite a World Health Organization (WHO) estimate of the need to detect around 14,000 TB cases annually, the nation only has 7,000 to 8,000 registered patients.

Statistics of TB cases in Sri Lanka remains woefully insufficient due to a strained healthcare system, altered patient behavior, low rates of child case identification, high mortality, inadequate referral pathways for suspected outpatient TB cases, limited contact screening, and a fragile public-private partnership. Nonetheless, Sri Lanka, with its robust healthcare infrastructure, aspires to reduce TB incidence from 65 per 100,000 (the 2015 baseline) to just 13 per 100,000 by 2035, aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The WHO in Sri Lanka consistently supports the National Tuberculosis Programme by implementing latent TB screening and management programs. An ‘Electronic Patient Information System’ module dedicated to latent TB has been developed, and the diagnosis of TB infection in high-risk groups has been improved through Interferon-Gamma Release Assays, advanced whole-blood tests. Despite these efforts, the fear of TB within the community persists.

Dr. Mizaya Cader, a Consultant Community Physician in the National Program for Tuberculosis Control and Chest Diseases, shed light on patient reluctance to seek TB treatment. She stated, “When patients have a persistent cough, they often don’t link it to TB and hesitate to seek treatment initially. However, the challenge arises upon diagnosis. Typically, when a family member contracts TB, comprehensive screening and open communication are practiced. It is at this point that the stigma associated with TB becomes evident. Surprisingly, it’s not just patients but also those around them, including healthcare professionals, who exhibit stigmatizing behavior due to a lack of awareness about the disease. TB, like COVID-19, is an infectious ailment with a protracted incubation period. When detected early, it’s treatable.”

Dr. Cader said, “Historically, TB was linked to individuals with limited nutritional means, earning it the label ‘disease of the poor.’ However, in today’s context, TB often coincides with conditions compromising the immune system, like diabetes and kidney diseases, making it a potential threat to anyone. The crucial message here is that anyone can be susceptible to TB, so it’s vital to ignore the stigma, seek help when needed, and encourage others to do the same. Stigmatization can lead to severe consequences, including depression and other social issues for those diagnosed.

“Many are hesitant to visit a chest clinic when experiencing symptoms. In fact, my survey showed that only 9% of symptomatic patients sought care at chest clinics, with most opting for nearby hospitals or dispensaries. In a tragic incident in Puttalam, an educator reportedly took their own life after a TB diagnosis. Such occurrences should be unimaginable in this age of readily available information,” she said.

However, it is evident that the health sector does its best to provide treatment to TB patients amid the social stigmas surrounding it. This is also a common concern amongst many marginalized communities such as the LGBTIQ communities as there is already an array of social stigmas surrounding them.

Speaking on the mechanisms in place, Public Health Inspector, of the District Chest Clinic Ratnapura, D.W.M.K.I.B. Wickramasinghe told us that the MOH does their best to maintain the privacy of the confidentiality once diagnosed. “The procedure is that we notify the MOH, and the PHI in the area will go to the house of the patient and try to find the contact in a very discreet manner. Most PHI’s go to their premises casually so that the neighbor is not alarmed. We provide counselling to the patient and their families prior to the treatment as they are usually mentally down at the time of diagnosis. Then we complete the 6 month treatment discretely. Even after we stay in touch for any further support. It is important to develop a friendship with them”, he added.

When asked about the biggest challenges faced Wickramasinghe told us that, “one challenge is that sometimes patients don’t continue treatments, they come for about 2 months and stop, it is our responsibility to get them to come for the chest clinic. If they are not contactable, we will go to their residence and see what is wrong. Some patients live in a house with only one or two rooms with like 10 family members, creating a high risk of spread. So we then have a possibility to get them to the ward and complete their treatment. We also have awareness programs for the community desensitizing them on TB.” The other biggest challenge we are facing is the difficulty in finding cases and in the case of most patients it is too late by the time they come to the chest clinic. This is mostly because of the lack of awareness. There is a big gap between the estimated number of patients and those recorded. And each undetected patient is surely spreading it to more people. This is definitely a burning public health issue.”